Our whole team was startled by this data about IT degree enrolments

I was recently browsing the Dept of Education, Skills and Employment website and stumbled across the 2019 university student data. These days, nearly all IT workers have degrees so unsurprisingly graduates comprise the majority of the supply of new IT workers. Skilled immigrants are our secondary source, more about them later.

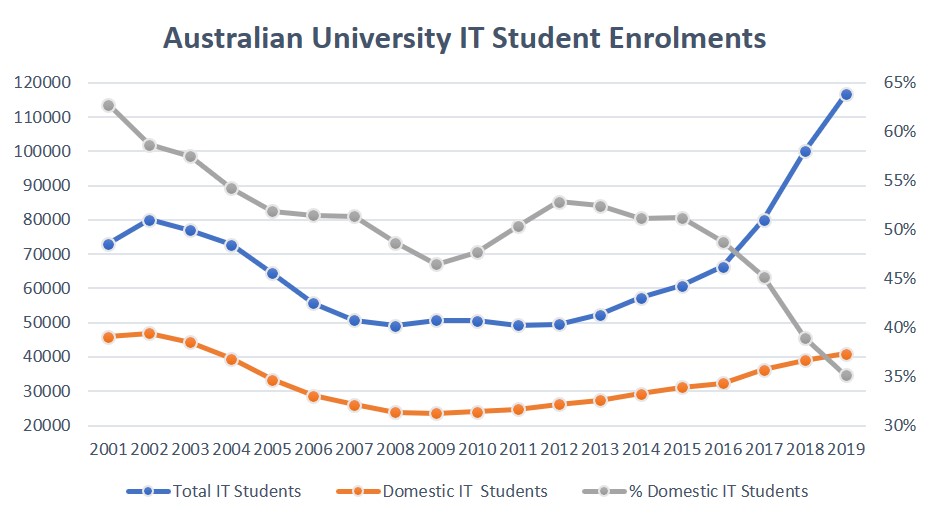

Interestingly there about 1.6M university students in Australia, with around two-thirds local students and one third overseas students. In the IT courses, Australian universities have overseen a stunning growth in student numbers growing from 60,731 in 2015 to 116,623 in 2019. This 92% increase compares to an overall student number increase of 14% for the same period.

So how did we pull off this miracle?

Obviously this wasn’t an accident, our IT student number were heading in the wrong direction for a decade, dropping from around 80,000 in 2002 to an average of less than 50,000 from 2008 to 2013. No wonder action had to be taken – and that action was more foreign students. Many, many more!!!

In 2015 we had 29,614 foreign students studying IT, in 2019 this had almost tripled to 75,643, meaning around two-thirds of IT students studying in Australia are now from overseas – I had no idea it was this high.

Due to Covid, that flow of foreign students has largely stopped. (200 words into an article before I mentioned Covid – that’s a new record surely)

How big is the impact?

The data for 2020 has not been released. At this stage one of our best clues on the extent of the student losses comes from this Sydney Morning Herald article highlight that student accommodation numbers are down 70%-75%. Assuming some of those that remain in accommodation are local students from regional areas I would expect we are currently looking at an even higher rate of loss.

The real impact, however, is that many of those who remained enrolled have returned to their home counties and are studying remotely. They are now almost certain to secure their first job overseas and thus far less likely to ever return and join the Australian workforce. That represents tens of thousands of skilled workers permanently missing from our economy. And that is just the impact from the cohort of student enrolled in 2020.

And what of future enrolments?

If you are paying $100k for a degree and a similar amount in living expenses over a 4 year period, you want the best possible educational outcome. These decisions are not made quickly or lightly.

Looking to the future, if you are a potential overseas student and currently considering your options for future study, you would be unlikely to consider a country where the borders have been shut for a year. Therefore, the effects are likely to be felt in graduate numbers not only in the short term but at least as far as 2025. And the reduction in graduates in the interim period will affect available talent in the long term.

So, with a significantly reduced graduate flow for the foreseeable future and the absence of the 110,000 skilled immigrants who normally arrive on our shores every year, the supply of IT workers will be significantly impacted.

Does it matter?

Well, that depends on demand….and demand is looking very solid. There are now 14% more job ads on Seek.com.au than before the pandemic lockdown last March. At Balance Recruitment, the team is really busy, all of our clients are now hiring again – even those from the worst affected industries. And business confidence indices, both locally and internationally are now higher than pre-pandemic.

Yes there are downside risks, many of them, but on balance I’m struggling to come up with scenarios where we don’t experience a medium to long term skills shortage. Yes, the immigration tap will be turned on again in the short to medium term but by that stage we will have missed out on 200,000 new skilled arrivals and surely as much as that again in graduates.

On the upside, it is likely local students will not be able to take gaps years and will immediately enrol, whilst universities will accept more local students (by lowering entry standards) to fill their empty lecture theatres; but is filling a short fall with moderately well-educated students really what we need?

I would love to hear your thoughts. Where will the new knowledge workers come from? Is there an issue? What’s the solution?

I’ll write next month about what steps can be taken to deal with this.